|

|||||||||

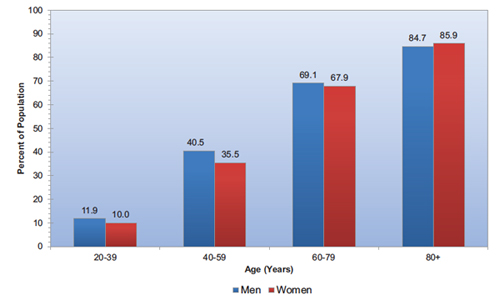

Should eggs and bacon be on your kid’s breakfast menu? Parents and nutrition experts agree that skipping breakfast is not a good idea for children or teens before they head off to school or work. But undoubtedly many of us think that the traditional breakfast of eggs, bacon and a tall glass of OJ is a good way to start the day. Certainly, that meal provides a lot of protein and vitamin C but it is not ideal––in fact it is an unhealthy diet. Maybe white bread toast with butter and jam or jelly on it, or a sweet roll, or pancakes drenched in syrup are also on the menu––they too provide less than ideal nutrition. Here is the science: The atherosclerosis that narrows arteries and causes cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) usually starts in childhood and continues to increase in severity throughout life. Bacon is high in saturated fat, sodium (salt), and is a processed red meat. These attributes are associated with development of CVDs, diabetes and cancer. Like bacon, eggs are high in cholesterol and eating too many of them may also speed the development of CVDs. The fruit juice, jam and jellies are high in sugar and low in the healthful fiber found in whole fruits that slows the metabolism of sugar and counteracts the effects of a high level of sugar in the diet. And white bread is a processed food that is metabolized rapidly. It also contributes to a spike in insulin, and may lead to hunger if it moves too much sugar out of the bloodstream. Long-term, high amounts of sugar and highly processed carbohydrates, like white flour and white potatoes, lead to the development of insulin resistance and diabetes. Red Meat and Processed Meat and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) In 2015, the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs Programme classified the consumption of red meat as probably carcinogenic andprocessed meat was classified as carcinogenic to humans, based on sufficient evidencethat the consumption of processed meat causes colorectal cancer. The IARC concluded that each 50-gram portion of processed meat eaten daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%.1011 If this small increase in cancer risk is of concern then it is best to avoid bacon, sausage, lunchmeats, hams, hot dogs and other processed meats. Another autopsy study of young people, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1998, found that the prevalence of fatty streaks in the coronary arteries increased with age from approximately 50% at age 2 to 15, to 85% at age 21 to 39. The prevalence of raised fibrous-plaque lesions in the coronary arteries increase from 8% at ages 2 to 15 years to 69% at ages 26 to 39.15 A more recent study among U.S. service men who died from accidental injuries found lower levels of coronary arthrosclerosis.16 While not entirely comparable to the earlier studies, autopsies carried out between 2001 and 2011 found coronary atherosclerosis of any severity among 8.5% of those studied. It was minimal in 1.5%, moderate in 4.7%, and severe in 2.3%. The low levels of atherosclerosis may be accounted for by the low levels of risk factors present in this young (average age 27) population compared to the general public. Only 4% were obese, 3% smoked, 1% had high blood pressure, 0.7% had cholesterol levels higher that 240 mg/dl, and 0.2% had high fasting blood glucose levels. The 2001-2011 studies of U.S. service men should not be considered a reason for complacency about cardiovascular disease. A high proportion of the older study subjects showed signs of atherosclerosis. Those age 40 or older were seven times more likely to have coronary atherosclerosis than those age 24 and younger. Among those ages 30 to 39 the prevalence of aortic and/or coronary atherosclerosis was 22.1% and among those age 40 or older it was 45.9%. As shown on the chart below, the progression of cardiovascular disease with advancing age was documented in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that found that the percentage of Americans with cardiovascular disease progressed with age.17

Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in adults ≥20 years of age by age and sex (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2009-2012). These data include coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke and hypertension. Source: National Center for Health Statistics and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.Back to top

In the U.S. most children get two to three times the protein they need daily, and there is no good evidence that protein bars or powders that provide more than the recommended minimum of about 10%-15% of total calories a day are beneficial. For teens and young adults this is the equivalent of about 46 grams per day for women and 56 grams for men. One way to determine an adult’s RDA for protein, is to multiply weight in pounds by 0.36. What to avoid: red meat, foods high in sugar, and many processed foods, because they are likely to be high is sodium, sugar and saturated fat. Unprocessed and minimally processed breakfast foods can include raw or cooked fruits, vegetables, whole grains like oat meal, and brown rice, and legumes like lentils, beans, chick peas, peanuts and soybeans. The best food to buy is whole unprocessed and plant-based produce that does not need a Nutrition Facts Label (NFL). Processed foods are attractive because they have long shelf life, convenience and can be low cost. By reading the nutrition facts label it is possible to select the healthiest versions of processed breakfast foods: those high in whole grains, high in fiber and low in sugar, sodium and saturated fat. Sugars come in many forms. The ingredients listed on food-product labels that end in “-ose,” such as glucose, sucrose, galactose, dextrose, lactose, fructose or maltose, are sugars. They are healthful components of food when found naturally in milk, fruit and vegetables. But sugar becomes unhealthy when added in large amounts to foods, most often in the form of sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup. The NFL provides a listing of total sugar and separately list the amount of the healthy sugars found in fruits and vegetables and the amount of unhealthy added sugars. Calories per serving: The NFL will list the calories in a serving to reflect the amounts of food people actually eat. “Low calorie” on the label means 40 or fewer calories per serving, “reduced calorie” means 25% fewer calories than in a same size serving of the original food; and “light or lite” means 33% fewer calories than in a same size serving of the original food. Fat: “Reduced fat” on the label means at least 25% less fat per serving compared to the original food; “low-fat” signifies 3 grams of fat or less per serving; “fat-free” is 0.5 grams or less fat per serving; and “trans-fat free” signifies 0.5 grams of trans fat or less per serving. Sodium: “Reduced sodium” means 25% less sodium than in a same size serving of the original food; “light in sodium or lightly salted” signifies 50% less sodium than in a same size serving of the original food. “Low sodium” means 140 mg or less per serving; “very low sodium” means 35 mg or less per serving; and “salt/sodium free” means less than 5 mg sodium per serving. “No salt added or unsalted” means no salt was added in processing but it does not mean that the product is sodium-free. Vitamins and minerals: “Excellent source of” means the food has at least 20% of the daily value of that vitamin or mineral per serving: “good source of” means the food has 10-19% of the daily value; “enriched with” lists added vitamins and/or minerals; and “fortified with” signifies adding vitamins and/or minerals that are not in the product naturally. Consumers should be aware that while it is not likely, it is possible to get too much of a specific dietary supplement from fortified foods. The healthiest breakfast cereals are 100% whole grain. They vary markedly in their content of sodium, but many are relatively high in sodium—it is preferable to choose those with under 180 milligrams per serving (sodium can be as high as 400 milligrams per serving). Sugar content is also highly variable with 0-1 gm. per serving up to 20 gm. per serving––aim for 5 gm. of added sugar or lower. Be aware that the key health metric is the amount of added sugars, for example, traditional raisin bran is a healthy cereal in spite of high total sugar because the sugar in raisins does not have the unhealthy implications of added sugars, however some added fruit in cereals may be sugar coated so read the label to determine added sugar. Fiber content is also quite variable from 0 up to 14 gm. per serving––aim for 5 gm or more per serving. These healthy cereals, that are low in sugar and saturated fat and high in whole grains and fiber, are listed in alphabetical order: All-Bran, Cheerios, Fiber One, GOLEAN (Kashi), Grape Nuts, Shredded Wheat, Total, Wheaties, and Wheat Chex.32 Also keep in mind that although the health effects of dairy foods are still not fully understood, choosing non-fat milk and adding no sugar from the sugar bowl is probably the best way to have your cereal. When using a soy, almond or any other nondairy beverage, select one that is fortified with calcium and vitamin D and is unsweetened, or at least low in added sugar.33 Summing up: 1 Bernstein AM, Sun Q, Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Willett WC. Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2010;122:876–883. 2 Larsson SC, Orsini N. Red meat and processed meat consumption and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 179: 282-9. 3 Abete I, Romaguera D, Vieira AR et al. (2014) Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Nutr 112, 762–775. 4 Micha R, Wallace S, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121:2271–2283. 5 Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L. Components of a Cardioprotective Diet: New Insights. Circulation. 2011;123:2870-2891. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATION AHA.110.968735

6 Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Apr 9;172(7):555-63. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2287. Epub 2012 Mar 12. 7Ornish D. Holy Cow! What's Good for You Is Good for Our Planet Comment on “Red Meat Consumption and Mortality”. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):563-564. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.174

8Wang X, Lin X, Ouyang YY, Liu J,Zhao G, Pan A, Hu FB. Red and processed meat consumption and mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016 Apr;19(5):893-905. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015002062. Epub 2015 Jul 6. 9 Etemadi A, Sinha R, Ward MH, et al. Mortality from different causes associated with meat,

heme iron, nitrates, and nitrites in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study: population cohort study. BMJ 2017;357:j1957.

10WHO. Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. October 2015. http://www.who.int/features/qa/cancer-red-meat/en/ 11WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Press Release No. 240. October 26, 2015. https://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2015/pdfs/pr240_E.pdf 12Berenson GS ed. Bogalusa Heart Study: Evolution of Cardio-metabolic Risk from Childhood to Middle Age. Springer, 2011.

13 Enos WF, Holmes RH, Beyer J. Coronary disease among United States soldiers killed in action in Korea: preliminary report. JAMA. 1953;152(12):1090-1093. 14McNamara JJ, Molot MA, Stremple JF, Cutting RT. Coronary artery disease in combat casualties in Vietnam. JAMA. 1971;216(7):1185-1187. 15Berenson GS, Srinivasan S, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between cardiovascular multiple risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. N Engl J Med1998;338:1650-6.

16Webber BJ, Seguin PG, Burnett DG, Clark LL, Otto JL. Prevalence of and risk factors for autopsy-determined atherosclerosis among US service members, 2001-2011. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2577-2583. 17Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despr.s J-P, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jim.nez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38-e360. 182015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/ 19Mozaffarian D. Nutrition and cardiovascular disease and metabolic diseases. In: Mann DL, Zipes 20 Berger S, Raman G, Vishwanathan R, Jacques PF, Johnson EJ. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(2):276-294. 21Fuller NR, Sainsbury A, Caterson ID, Markovic TP. Egg Consumption and Human Cardio-Metabolic Health in People with and without Diabetes. Nutrients. 2015 Sep 3; 7(9):7399-420. Epub 2015 Sep 3. 22 Fuller NR, Sainsbury A, Caterson ID, Markovic TP. Egg Consumption and Human Cardio-Metabolic Health in People with and without Diabetes. Nutrients. 2015 Sep 3; 7(9):7399-420. Epub 2015 Sep 3.. 23 Mozaffarian D, Ludwig DS. Dietary Cholesterol and Blood Cholesterol Concentrations—Reply. JAMA.2015;314(19):2084-2085. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12604

24 Levin S, Wells C, Barnard N. Dietary Cholesterol and Blood Cholesterol Concentrations. JAMA.2015;314(19):2083-2084. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12595 25 Choi Y, Chang Y, Lee JE, et al. Egg consumption and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic men and women. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Aug;241(2):305-12. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.036. Epub 2015 Jun 3. 26 Zhong VW, Van Horn L, Cornelis MC, et al. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1081–1095. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1572

27Fuller NR, Sainsbury A, Caterson ID, Markovic TP. Egg Consumption and Human Cardio-Metabolic Health in People with and without Diabetes. Nutrients. 2015 Sep 3; 7(9):7399-420. Epub 2015 Sep 3. 282015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/ 29http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2002/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-for-Energy-Carbohydrate-Fiber-Fat-Fatty-Acids-Cholesterol-Protein-and-Amino-Acids.aspx 30http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2019/DRI-Tables-2019/1_EARV.pdf?la=en

31Levine, Morgan E. et al. Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer,andOverall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metabolism , Volume 19 , Issue 3 , 407 - 417 |

|

|||